Making Web Cache Deception critical in 30 minutes

Web Cache Deception, first discovered (I think…) here, is a rare attack class that enables an attacker to trick users into storing sensitive information in a server-side cache for later retrieval.

Unfortunately, throughout all my adventures so far, a total of 0 applications have responded positively to my Web Cache Deception probes. Despite this, the topic has always hung about in the back of my mind as something exciting to test for if I can find any reference to the presence of a server-side web cache.

The following write-up recounts how I detected, probed and successfully exploited a Web Cache Deception vulnerability in my first-ever SynAck Red Team engagement, reaching a critical impact in a record-breaking 30 minutes.

Spotting the Vulnerability

Web Cache Deception is actually relatively trivial to spot and therefore my methodology for detecting it is equally simplistic. Two requirements must be met:

The application must use a server-side cache that checks file extensions rather than relying on caching headers. E.g.

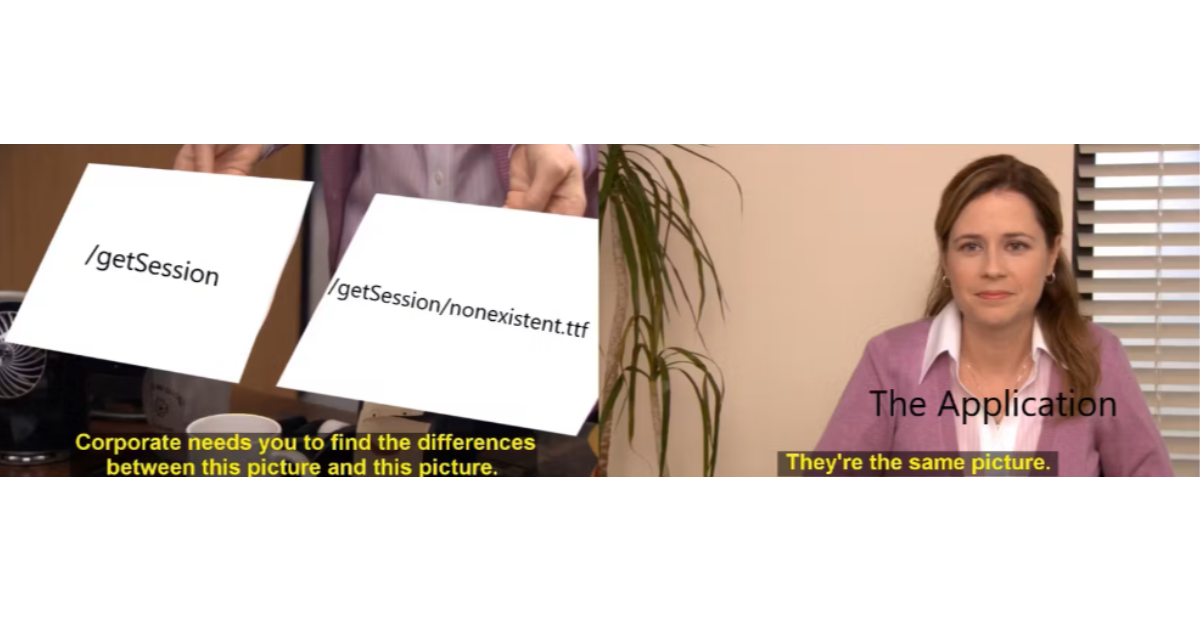

/favicon.icogets cached but/homedoes notThe application must ignore anything after a valid path. E.g. a request towards the completely valid path

/my-accountwill respond in exactly the same manner as the “usually invalid” path/my-account/arbitrary

If you spot both of these behaviors you have a really good shot at finding a Web Cache Deception vulnerability and you should dive into the rabbit hole! In my case, the application made things fairly obvious on the very first request I made to /. That’s right, it responded with an obvious caching header Server-timing: cdn-cache; desc=MISS. To add to the good news, I also spotted that this header is extremely suggestive of Akamai, something I hadn’t had a chance to work with yet but knew had lots of interesting caching behaviors…

So we have a cache. My first thought after seeing cache and akamai (according to my, as ever, extremely professional notes) was to go for Web Cache Deception.

The next step is to see how the cache behaves, and after a bit of prodding it was clear that static files like /service.js were getting cached, but anything without a file extension was not. This heavily implied that the file extension was likely used to determine whether or not to cache a resource, #1 on the Web Cache Deception methodology checklist.

So far so good… the next thing I tried was to send a request to /services.js and compare it to /services.js/somethingrandom. These two requests returned exactly the same response which meant that the application itself, was ignoring the trailing /somethingrandom in the path, and making the assumption that I was requesting services.js. This is requirement #2…. it was time to dig deeper!

Building an exploit

The preceding took me something like 20 minutes to figure out, so at this point, I was pretty excited to test this out on some sensitive endpoints…

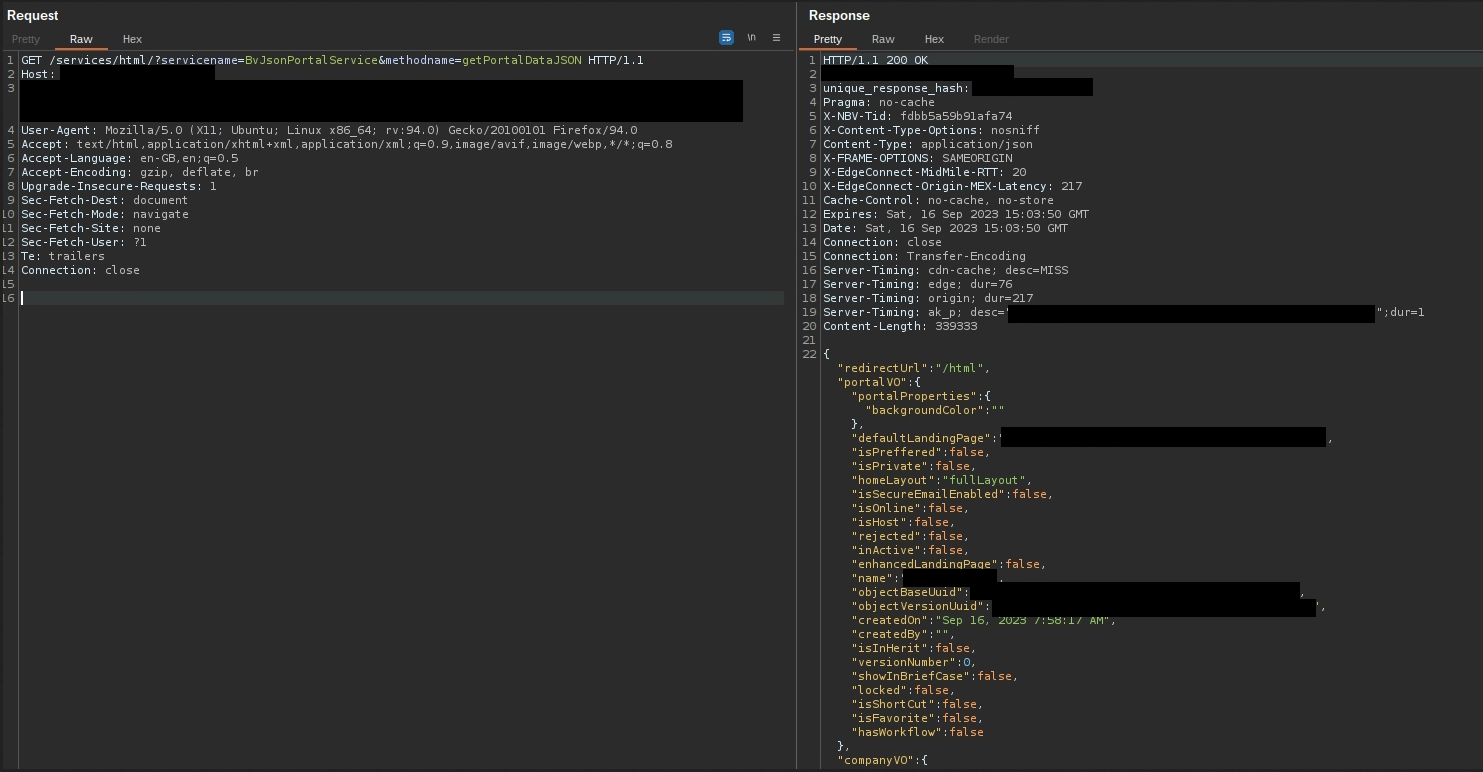

The application strangely served most of its functionality on a single endpoint (/services/html) and simply passed a couple of parameters to interact with, I assume, various endpoints on some back-end API. In any case, this design choice made my target selection fairly easy…. I needed to see if I could cache a sensitive response on the /services/html endpoint.

After logging in to the application (an important note, as most sensitive information is tied to a user…..) as an administrator, I found the following endpoint /services/html?servicename=BvJsonPortalService&methodname=getPortalDataJSON. This endpoint returned amongst other things, the active user’s session token and CSRF token… A perfect target. Given that the endpoint did not have a file extension, the application was not caching this page (for obvious reasons).

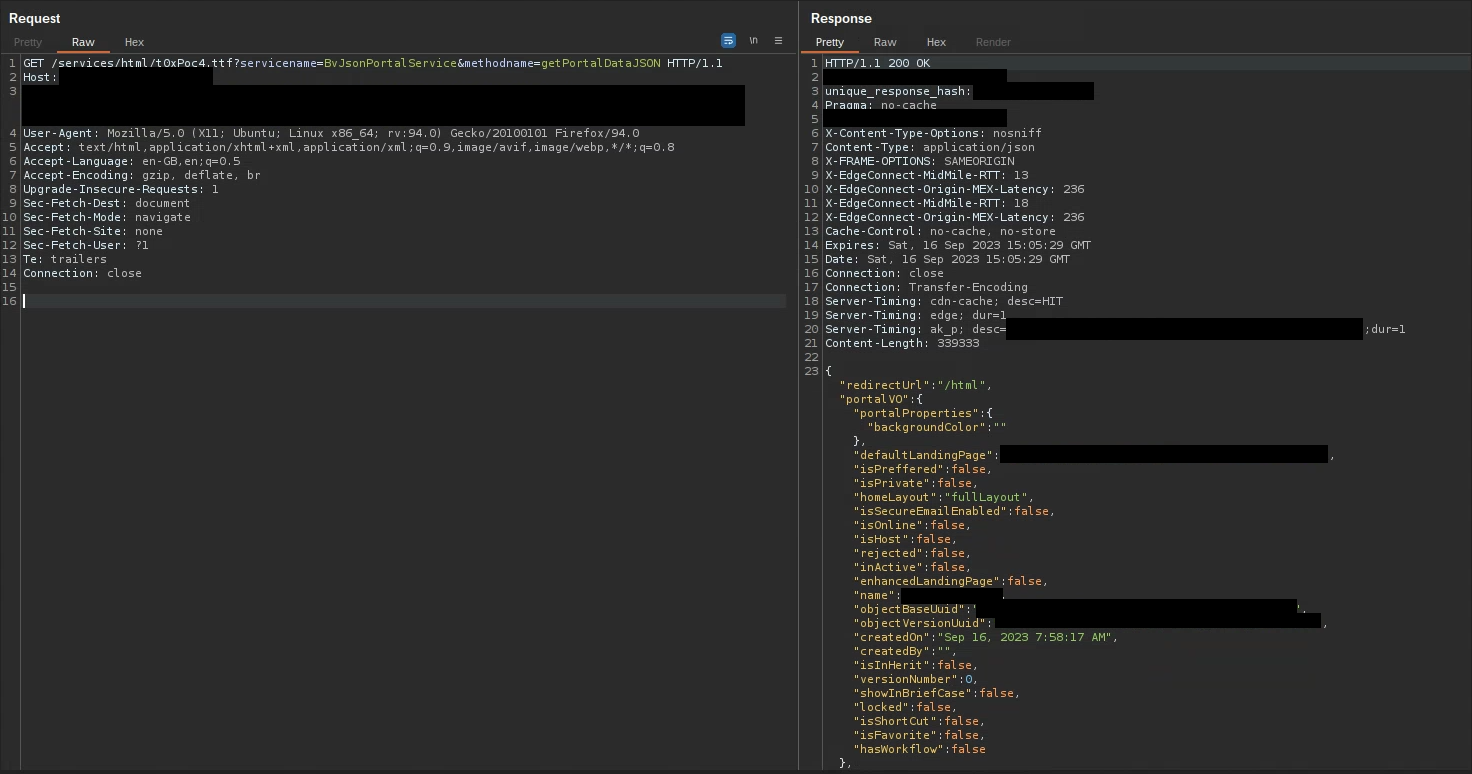

Given that the application has a lot of .js files that were getting cached, my first thought was to attempt the following request twice in a row /services/html/t0xodile.js?servicename=BvJsonPortalService&methodname=getPortalDataJSON. However…. this did not work. The application simply responded as normal with Server-timing: cdn-cache; desc=MISS. Disappointing to say the least…. Maybe .png, .html or .madeup? No, no and no…. At this point, I was about to start questioning my logic up until this point to see where I went wrong. However, just before I did, I sent the request to Burp Intruder and ran a quick check against a long list of file extensions… To my surprise, I had one HIT! .ttf to the rescue!

That’s right believe it or not, the second .ttf request resulted in Server-timing: cdn-cache; desc=HIT! The application was serving the normal response for the /services/html?servicename=BvJsonPortalService&methodname=getPortalDataJSON endpoint and the cache was storing it! To confirm that the cache is storing the sensitive response data (don’t forget that we’ve just stored the active user’s session cookie and CSRF token in the cache) on an attacker-accessible endpoint, I repeated the request, without any session cookies, to ensure it could be reached unauthenticated (by an “attacker”). This of course… worked like a charm!

Hey presto, that’s it! We have PoC!

Attack Walkthrough

Web Cache Deception can seem confusing if you’ve never seen it before. The following explains the entire “attack flow” from the perspectives of the victim user and the attacker.

The attacker creates a malicious link that will store the victim user’s session details. E.g.

/services/html/<attacker-known-endpoint>.ttf?servicename=BvJsonPortalService&methodname=getPortalDataJSONThe attacker tricks an authenticated victim (ideally an admin of course) into visiting the link

The application responds as normal with the user’s session details and the cache spots the

.ttfextension and decides to cache the response against the/services/html/<attacker-known-endpoint>.ttf?servicename=BvJsonPortalService&methodname=getPortalDataJSONendpointAt a later date (ideally before the cache entry expires) the attacker (who is not authenticated with the application) visits the malicious link

The cache, sees the attacker trying to reach the same page that the admin user visited and serves the cached response to the attacker. Which of course… contains the admin’s session details

The attacker can trivially reconstruct the admin’s session cookie and goes from unauthenticated to application administrator in a single link!